The world was shocked in 1962 when Rachel Carson published her book, Silent Spring, announcing how birds are no longer singing in the sky due to toxic pesticides. Carson called attention to the need for people to be aware of what we are doing to our environment and launched what would come to be known as the modern environmental movement.

What was left out of the narrative was the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on certain communities, particularly minority communities. This effect has been termed environmental racism. Environmental racism refers not only to the increased risk of damage minority communities face during natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, but also to the health impacts they face as a result. In a review of 20 years of data, The National Conference for Community and Justice notes that “more than half of the people who live within 1.86 miles of toxic waste facilities in the United States are people of color,” putting them at increased risk of developing headaches, difficulty breathing, irritated skin and eyes, and other illnesses. EPA data shows black children have double the rates of asthma and heart disease compared to white children, and individuals living in minority communities are at much higher risk for disease, a point that was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

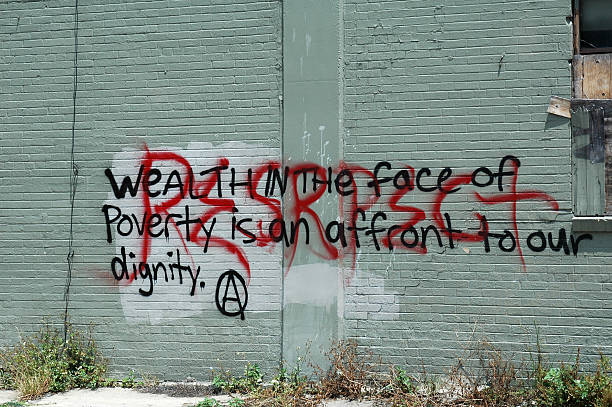

These alarming trends have brought about a call for environmental justice, a term describing the need for equality in execution and enforcement of environmental regulations and policies. Dr. Robert Bullard, also known as the “Father of Environmental Justice,” has devoted his career to raising awareness of bringing to the spotlight this narrative. He has focused specifically on how minority communities, mainly communities of color, are disadvantaged in terms of health and overall well-being by the location of affordable housing. Dr. Bullard notes, “America is segregated and so is pollution. . . .Today, zip code is still the most potent predictor of an individual’s health and well-being.” Already the victims of historical and continued systemic racism, such as underinvestment in neighborhood schools and limited access to nearby stores selling healthy foods, minority communities sustained added damage through the close proximity to environmental pollutants and toxic waste facilities, due to historical policies of redlining.

To address these concerns, in February 1994, President Clinton issued Executive Order 12898. The goal of this Executive Order was to “focus federal attention on the environmental and human health effects of federal actions on minority and low-income populations with the goal of achieving environmental protection for all communities.” Executive Order 12898 has been in place for 27 years. Despite this action, the crisis of environmental justice has never been more pronounced.

Fortunately, we are starting to take meaningful steps to address both the environmental crisis and associated environmental racism. President Joe Biden promised equal laws and policies that would root out systemic racism, including environmental racism, during his Presidential campaign. Biden promised to establish an Environmental and Climate Justice Division within the Department of Justice. Already, President Biden passed an Executive Order that establishes an interagency council on environmental justice within the White House, creates an office at the Health and Services Department for health and climate equity, and follows through with his promise, forming an environmental justice office within the Department of Justice. In addition, the Biden Administration has made a promise to return to science and fact when dealing with all issues concerning the environment, from social issues like environmental justice to the existential threat of climate change.

The efficacy of these steps remains to be seen as our country wrestles with extreme partisanship and climate change denial. National organizations, like Greenaction, operate as a part of what is known as the environmental justice movement. These organizations work with communities one-on-one on a local level and offer solutions that function outside of the highly partisan national discourse. Specific cities are also making environmental justice a priority. As of 2019, New York City, San Francisco, and Fulton County, Georgia have all enacted concrete environmental justice policies. San Francisco, a city known for its priority for green space and parks, has earned more than $12 million in grant money since the policy was enacted in 2000. Given the magnitude of the challenges presented by the issues of environmental racism, a combination of local and federal efforts are required to create lasting policy that creates meaningful change in affected communities.